|

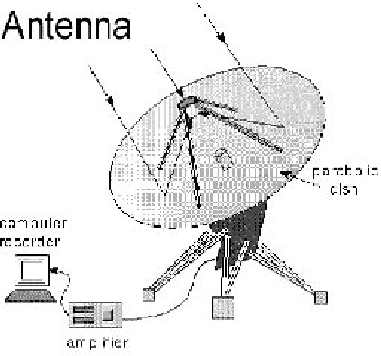

Radio telescopes are used to study naturally occurring radio emission from stars, galaxies, quasars, and other astronomical objects. As shown in the figure 1.2, most of the radio telescopes are dish-shaped, having metal parabolic reflecting surface to focus the incoming radiation to the focal point where the receiver is mounted. Radio telescopes have two basic components (1) a large radio antenna and (2) a sensitive radiometer or radio receiver. The sensitivity of a radio telescope i.e is the ability to measure weak sources of radio emission which in turn depends on the area, efficiency of the antenna and the sensitivity of the radio receiver which is used to amplify and detect the signal. The detected signal produces an electric current that is amplified, filtered for noise and then recorded.

A radio dish need not have a perfect surface; it can even be made of

separate panels covered by a perforated mesh. This is because the surface

accuracy of the reflector surface needs to be of

the order of ![]() of the observed wavelength. Therefore, while radio

telescopes designed for operation

at millimeter wavelengths need a high accuracy dish surface and are

typically only about ten meters or a few tens of meters across, those

designed for operation at centimeter and meter wavelengths need not be

so accurate and are made of larger size, such as the 45 m dish of the

Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT), north of Pune. There are also

expensive dishes built, such as the new 100 m Green Bank telescope

in the USA, which goes from low frequencies to

very high frequencies.

of the observed wavelength. Therefore, while radio

telescopes designed for operation

at millimeter wavelengths need a high accuracy dish surface and are

typically only about ten meters or a few tens of meters across, those

designed for operation at centimeter and meter wavelengths need not be

so accurate and are made of larger size, such as the 45 m dish of the

Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope (GMRT), north of Pune. There are also

expensive dishes built, such as the new 100 m Green Bank telescope

in the USA, which goes from low frequencies to

very high frequencies.